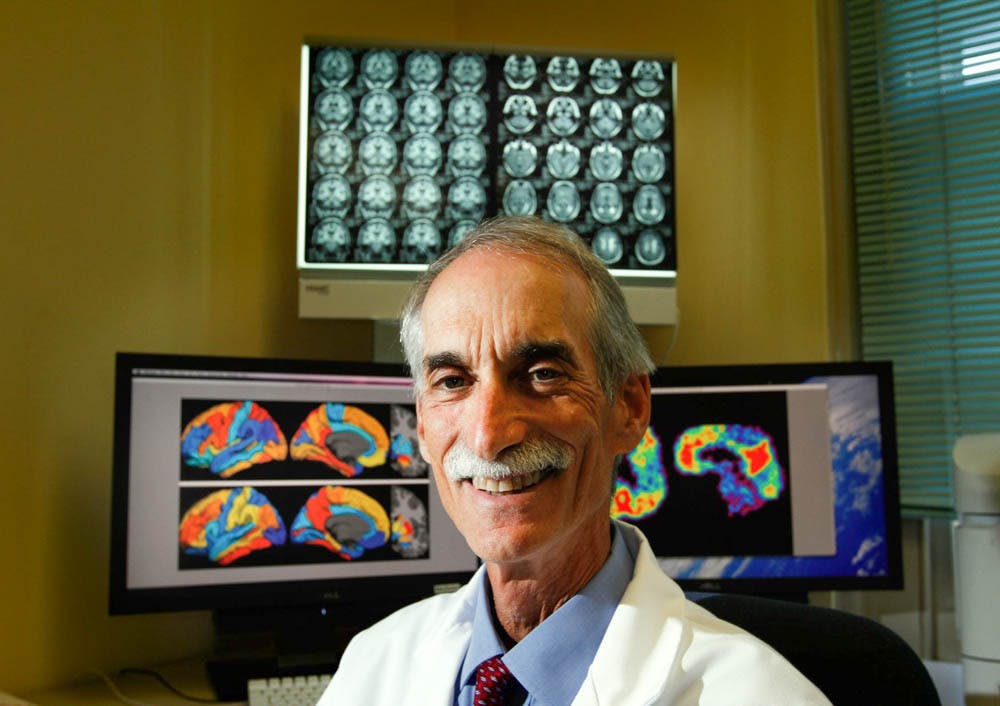

In the battle to understand Alzheimer’s disease, advancements in the testing and development of new technologies aim to provide stronger support for treatment. In collaboration with a number of other researchers and the Alzheimer’s Association, Professor of Neurology Stephen Salloway has been developing new criteria for the use of lumbar punctures, also known as spinal taps, to diagnose Alzheimer’s. Helping patients clarify whether they should undergo this procedure may allow them to detect the disease sooner and begin treatment as early as 10 to 20 years before memory loss occurs.

In the lumbar puncture procedure, a needle is inserted into the spine to extract cerebrospinal fluid. This process allows scientists to analyze the fluid, monitoring the levels of two proteins in the brain and body known as amyloid and tau, said John Hendrix, director of global science initiatives at the Alzheimer’s Association. As the levels of these two proteins fluctuate, they can provide earlier indications of forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s. This approach has become more prevalent as technologies, screenings and tests have advanced, Salloway said.

This upcoming form of testing can also increase accuracy in diagnosing patients, said Leslie Shaw, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the Hospital at the University of Pennsylvania, who is unaffiliated with the study. Alzheimer’s develops as a “continuum” with many stages, and research and testing allow for more educated and informed diagnoses at each stage to reduce rates of misdiagnosis and promote appropriate treatment, Shaw added.

Lumbar punctures are routine in Europe but are seldom used in the United States, Hendrix said. This may be a result of a fear of the procedure due to lack of awareness and knowledge of its mechanics — in reality, a spinal tap is a quick and effective procedure with few to no side effects, he added. Additionally, patients may doubt the procedure because of the belief that testing for dementia is futile due to the absence of a cure, Salloway said.

More conversation about this procedure could better educate the public and primary care physicians about the appropriate use of testing, which can lead to more accurate diagnoses and a more informed conversation on future treatment, Salloway said. “Alzheimer’s is probably our number one public health problem,” he added.

While some people who fear they have Alzheimer’s may wish to avoid treatment, the possibility of getting into a clinical trial early can greatly increase the chances and quality of treatment, Hendrix said. “It’s a really exciting time for this research, and one of the things that gives me great optimism is that these tools not only can help with more accurate diagnosis, but they will also help in finding new therapies,” he said.

In-depth PET scans to analyze tau proteins and blood and eye tests are also currently being researched as alternatives, Hendrix said. Blood testing is still being researched and is not currently in use, but may soon find applications as a preliminary screening test to lead into further procedures, Hendrix said. Other research being conducted at Brown involves using eye exams to analyze early retinal changes well before dementia and memory loss occurs, Salloway said.

“Care and support might not be a cure, but it does lead to better health, to better outcomes and to better quality of life,” Hendrix said.